In a earlier post, we talked about Bill’s favorite camera (his K.B. Canham View Camera), and why he likes using it. Since a view camera can somewhat complex to use, we decided to write a few posts on some of the interesting ways Bill has used the view camera to create the images he wanted to. If you are seriously interested in using view cameras, check out Leslie Stroebel’s book, View Camera Technique.

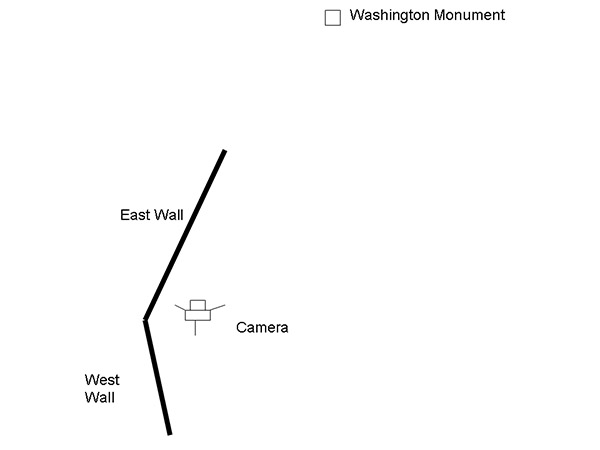

Bill’s photograph of the Vietnam Wall at Dawn is one of his best examples of how he used the view camera to create an image with specific qualities. The photograph was taken right before sunrise, shooting along the east side of the Vietnam Wall with the Washington Monument in the distance.

The layout Bill used for the photograph (not to scale, our PowerPoint skills are not that good) is shown in Figure 1. Essentially, the camera mounted on a tripod is set to shoot along the wall, while keeping the Washington monument in the field of view.

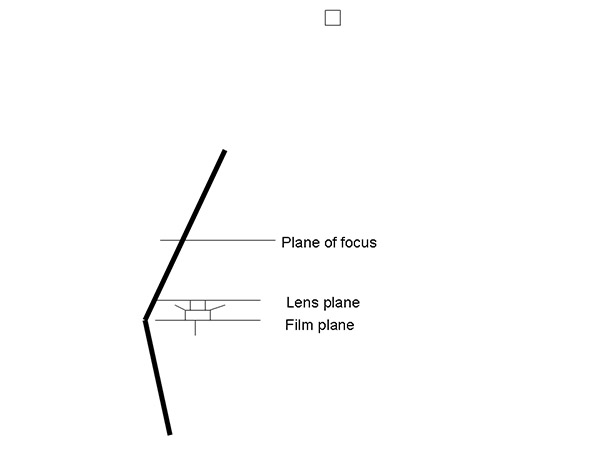

Figure 2 illustrates what you get when you use an SLR or point and shoot camera. With this type of camera, the plane of the lens is parallel to the plane of the film (or sensor in a digital camera). The plane of sharpest focus (what you focused on) is also parallel to the film. Everything in the plane of focus will be in sharp focus. The further you move away from the plane of focus, objects will appear more out-of-focus in the photograph.

If you were going to recreate Bill’s photograph using an SLR, the challenge is how do you keep both the closest part of the Wall and the Washington Monument in focus? You can do it to some extent by using a very small aperture to get large depth of field, but even that has its limitations.

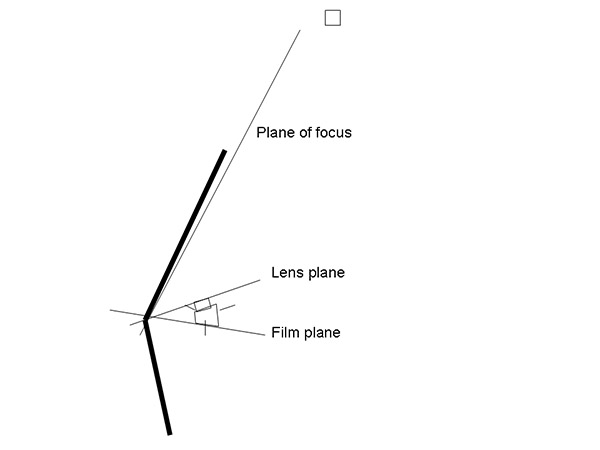

With a view camera – the lens plane and the film plane don’t have to be parallel. You can use camera movements to angle the film plane and the lens plane to change where the plane of focus will be. When done horizontally, the angling is known as “swing”. Done vertically it is known as “tilt”.

Below are two photos of the Canham. The first is with the lens plane parallel to the film plane (so similar to your standard camera in terms of the plane of focus), and the second shows the camera set for both front and rear swing. This is a more exaggerated swing than Bill used for the photo.

When the lens and film planes are no longer parallel, the plane of focus isn’t parallel either. This effect is known as the Scheimpflug principle (after Theodor Scheimpflug – an Austrian Army Captain). For his photograph of the Vietnam Wall, Bill applied primarily front and a little rear swing to change the plane of focus. As shown in figure 3, the entire wall and the Washington monument are in focus.

For many photographs, camera movements such as swing aren’t necessary. However, in certain circumstances, they are necessary to achieve your vision. Without the ability to swing the plane of focus, Bill’s The Wall at Dawn would be a nice photograph. With the swings – he was able to achieve your vision of a spectacular image with both the Wall and the Washington Monument in focus.